The Peculiar Problem Posed by the LED Lightbulb.

Can a sustainable economic model for long-lasting products be developed?

The light bulb that has been illuminating the fire-department garage in Livermore, California, for the past 115 years will not simply burn out; it will "expire." When it finally does, it won't be discarded but will be "laid to rest."

Tom Bramell, a retired deputy fire chief and the foremost historian of the Livermore light, emphasizes the importance of this terminology. The bulb has been almost continuously on since 1901. In 2015, it surpassed a million hours of service, earning the title of the world's longest-burning light bulb according to Guinness World Records.

Bramell, with his smoke-tinted eyes and hair, and a constant cough from smoke inhalation, embodies the life of a firefighter. His careful phrasing about the bulb's eventual end reflects the deep respect held by Livermore residents and fans worldwide, who keep an online vigil over the light. The bulb, manufactured around 1900 by Shelby Electric of Ohio using Adolphe Chaillet's design, has outlasted three webcams. Its specific makeup remains a mystery since it’s difficult to examine a light that’s always on. It is known to have a carbon filament about as thick as a human hair, akin to modern tungsten filaments. Initially a sixty-watt bulb, it now glows with the dimness of a nightlight.

Intriguingly, this incandescent bulb contrasts sharply with modern incandescents, known for their short lifespans. A typical drugstore incandescent would last roughly a thousand hours, whereas the Livermore bulb has far surpassed this. "We don’t build things today to last," Bramell remarks, capturing a sentiment many share.

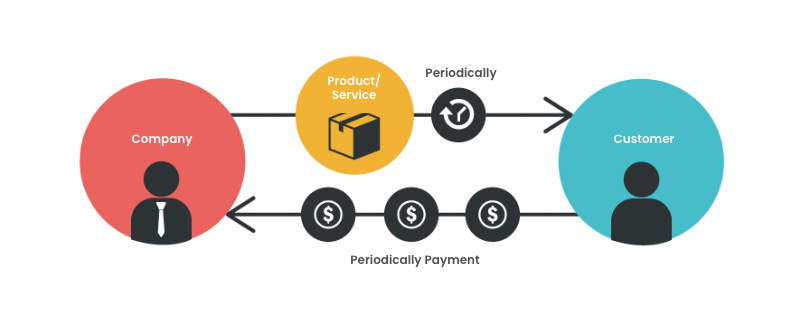

The challenge of building durable bulbs remains unsolved in terms of a viable business model, ironically the very issue shorter-lived modern incandescents were meant to address. However, the advent of LED technology, with its long-lasting bulbs, is challenging this norm. LEDs, utilizing semiconductor technology, often promise a lifespan of up to fifty thousand hours. As of early 2016, LED lamp shipments in the U.S. had surged by 375% from the previous year, capturing over a quarter of the market.

Yet, this shift presents a paradox: creating long-lasting products can undermine traditional business models reliant on frequent replacements. This dilemma dates back to 1924 when the world’s leading lighting companies formed Phoebus, the first global cartel, which aimed to standardize shorter bulb lifespans to boost sales. The reduced lifespan of bulbs was seen as an economic necessity rather than a technical improvement.

The Phoebus cartel's strategy of planned obsolescence, which once seemed like a sinister conspiracy, was actually a widespread economic principle by the late 1920s. The concept of planned obsolescence became deeply embedded in consumer culture, as highlighted by various historical sources, including Giles Slade's book "Made to Break."

LEDs, however, represent a significant departure from this trend. With their energy efficiency and long life spans, LEDs challenge the conventional economic model of obsolescence. Despite this, the lighting industry faces "socket saturation," where durable LEDs reduce overall bulb sales. Consequently, some companies have started producing shorter-lived, cheaper LEDs or are exiting the bulb market entirely, shifting towards more sophisticated lighting solutions.

The emergence of smart lighting, integrating LEDs with connectivity features, exemplifies this shift. Companies like Philips and Sony are developing products that go beyond simple illumination, embedding LEDs in multifaceted, connected systems.

Nevertheless, the LED revolution poses a significant question: can a sustainable economic model for long-lasting products be developed? Tim Cooper, a design professor at Nottingham Trent University, argues that achieving sustainability requires rethinking economic and policy frameworks to encourage durability and repairability.

Cooper suggests several policy measures to promote longer-lasting products, such as durability standards, tax incentives for repairs, and consumer education. This shift would involve a cultural change away from the pursuit of novelty and disposability.

The Livermore light bulb, now carefully preserved, symbolizes this tension between product longevity and modern consumer practices. Despite the economic challenges, the story of the Livermore bulb inspires a vision of a future where products are built to last, contributing to sustainability and reducing waste.